“Those who grew up whispering”

With Europe facing some of its biggest challenges since the end of the war, this VE Day (8 May) Eleni Karasavvidou reflects on the research of WW2 historians into the plight of the continent’s children orphaned and brutalised by the conflict, suggesting there may be profound lessons for how we respond to the present-day child refugees of other conflicts.

The current refugee crisis is not the first time that Europe has faced the problem of traumatised, unaccompanied children needing safe haven. Whereas today this is connected with the war in Syria and the refugee wave from the Middle East, 70 years ago it was connected with the conflict of Europe itself and the devastating reality left in the wake of World War 2.

According to official data, the mass killings and the dislocation of populations after 1945 resulted in a vast number of orphans. Statistics from the Red Cross, the UNRRA and some figures collected by national governments, amount to a combined total of more than 1,000,000 missing or unidentified children across the continent in the years immediately after the end of the war. In what was then Yugoslavia alone there were more than 280,000 orphans, including more than 10,000 children who were found in the forests trying to survive in conditions of absolute destitution.

In Germany the UNRRA had to ‘protect’ around 50,000 children, while in Greece, where by 1948 a devastating, full-blown civil war was being waged, around 40,000 children ‘participated’ in evacuation programmes. Half of these were sent by the Communist Party to orphanages in Eastern Europe; the other half to orphanages across Greece, or to childless families in the West.

Potential threat

This evacuation process was also happening in central Europe at the same time as national borders were being redrawn. In this context, children of minority ethnic communities, or children of defeated enemy states were treated as a potential threat. In this way, some nation-states seized the opportunity to ‘solve’ their minorities ‘problem’ with the end of the war. Alternatively, the children of the nation could be treated as a political weapon to construct the much needed cohesion and hegemony.

This child evacuation process was happening as a part of the political conflict surrounding it. Even children who had families, in the case of Greece for instance, were cut off from their parents and their homelands; with their upbringing assigned to political or even trafficking networks.

Many children of course lost their lives in the conflict, or in the Holocaust, but there was also a terrible psychological impact on the children imprisoned in concentration camps. According to the historian Mark Mazower, post-war research revealed a series of profound psychological traumas and deep disorders among orphans of the Holocaust.

Depression and passivity

War orphans in general were extremely suspicious of seeming acts of kindness; their liberation exposed them to a world where all ethics and poetry had died. These brutalised children were often violent to weak or younger children and could be dangerous in other ways too. At the other extreme, there was depression and passivity. Mazower refers to an incident where a group of nurses was negatively impressed by the behaviour of a group of young Jewish boys, who seemed unable to express any sign of neediness or trust. Faced with the disappearance or death of one of their group, this was taken for granted, with no display of emotion.

“Those who grew up whispering cannot suddenly start speaking their minds”

Europe had dehumanized its future. “Lets face it!”, said a girl from Czechoslovakia to a girl from England, “War did not create only heroes, it also created cowards … Those who grew up whispering cannot suddenly start speaking their minds”. The war had created an entire generation of anti-idealists, leading to a politics of cynicism, conformity and passivity, with the instinct for democratic engagement choked at a very deep level.

As Cannadine, in the Observer, wrote, commenting on Mazower’s research, ‘Anyone who wants to know why Europe ended up like this (a remote bureaucracy resisted by an evolving ultra-right populism), must seek answers in that period’.

Eleni Karasavvidou

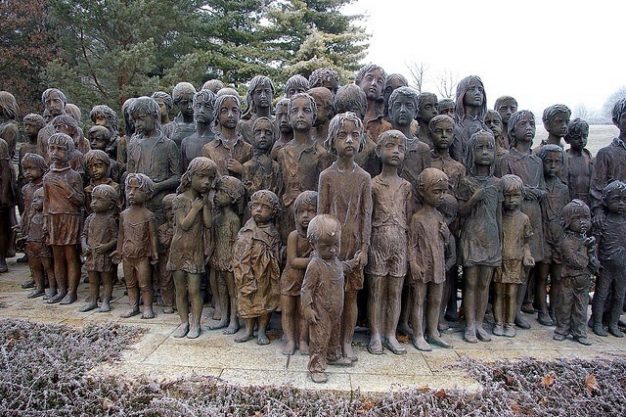

Photo by Peer Into The Past of the memorial, by sculptor Marie Uchytilová, for the children of Lidice, a small village in what was then Czechoslovakia, 82 of whom were murdered by the Gestapo N at the Chełmno extermination camp in 1942.

References

Van Boeschoten, Riki Danforth M. Loring 2011 Children of the Greek Civil War-Refugees and the Politics of Memory, the University of Chicago Press

Mark Mazower 1998 Dark Continent: Europe’s 20th Century, Penguin

Dorothy Marcadle 1949 Children of Europe New York, Victor Gollancz Ltd.